- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

In the late 1710s the French and English governments sought to tackle their respective national debts by promoting share trading in state-controlled joint stock companies: the French Compagnie d’Occident (Company of the West), also known as the Mississippi Company, and the English South Sea Company. In 1720 spectacular rises in share prices spread from the French to the English and eventually to the more diversified Dutch financial markets. Each of these bull markets was soon followed by a dramatic collapse in the value of shares. Together these three “bubbles” generated the first international stock market crash and ushered in the age of the bubble economy, which has characterized financial markets with remarkable regularity for three hundred years. The Mississippi and South Sea Bubbles, as well as the Dutch bubble, called windhandel, or trade in wind, also participated in another kind of paper economy: they generated reams of contemporary texts and images that still serve as cultural touchstones.

From the perspective of the history of economics, the financial innovations that drove the bubbles were inspired. The Scottish economist John Law, controller general of finances to the French regent, did not succeed in reforming the entire French economy, but he did manage to eradicate the national debt. Moreover, many European investors benefited greatly and only a few suffered major losses, since smart ones sold their stocks in time and many debts were forgiven. More importantly, at least in the long term, the 1710s ushered in financial innovations that could not be suppressed—and that still shape modern economies.

From the perspective of cultural history, however, the picture has been almost unremittingly bleak, a viewpoint crystallized by Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid (The great mirror of folly), a compilation of bubble texts and images—no two copies of which are exactly alike—published within weeks of the conclusion of the Dutch windhandel. Designed, as announced on the title page, as a “warning to posterity,” the volume is best known for its satirical prints. In the beautifully designed and produced Meltdown! Picturing the World’s First Bubble Economy, Nina L. Dubin, Meredith Martin, and Madeleine C. Viljoen bring the relatively underutilized tools of art history to bear on the study of the Tafereel. They argue convincingly that its prints should not be thought of as “mere illustrations” (12), but rather as manifestations of artists’ distinctive ability to “make visible the otherwise invisible forces of economic life” (13) and shape the reception of the events of 1720.

Conceived as a companion book to an exhibition that was to be held at the New York Public Library in 2020 but had to be postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Meltdown! is not a typical exhibition catalog. It is structured, as is the Tafereel, like a neoclassical play. It begins with a preface and acknowledgments that evoke the dedications and prologues of eighteenth-century plays. These are followed by a brief timeline and three chapters/acts: “Welcome to the Empire of the Imagination,” “Cast of Characters,” and “Collecting in Vain: Fools, Cons, Devils, and Dupes in ‘The Great Mirror of Folly.’”

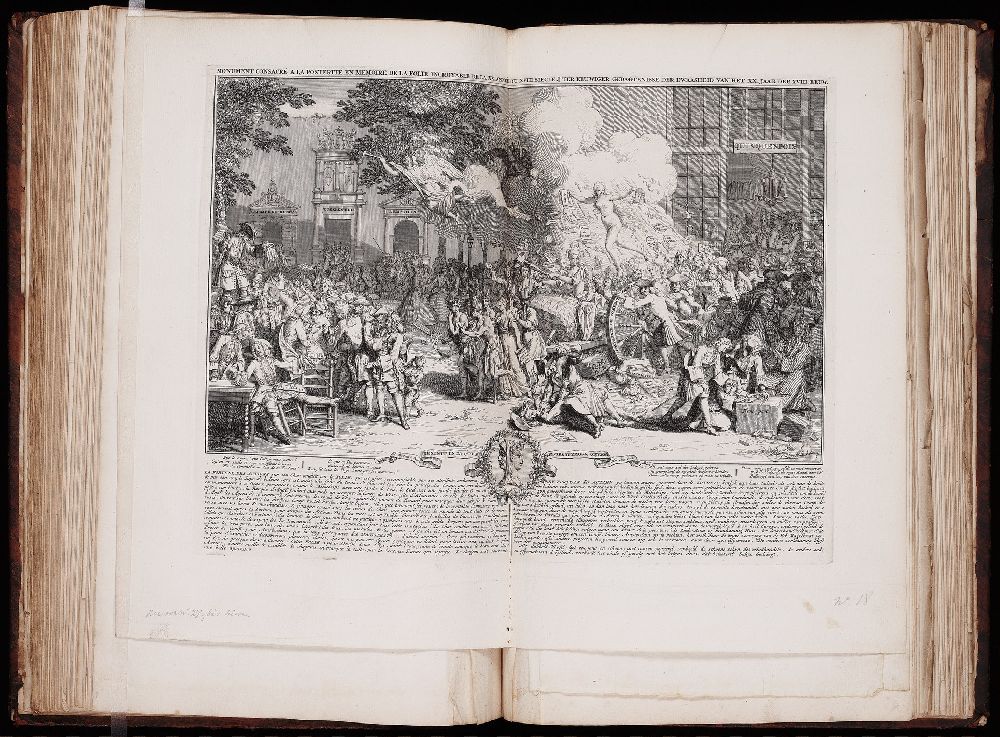

The phrase “Welcome to the Empire of the Imagination” refers to the invitation issued by Aeolus, Law’s mythical alter ego, to the people of Betica (France) in Montesquieu’s Persian Letters (1721). In this first chapter Dubin focuses on artists’ keen awareness of the relative value of paper—be it in the form of stocks or collectible prints—and of what could and could not be represented in an increasingly disembodied and fictional economy. In particular, she argues persuasively that artists’ ambivalence regarding the new economy—and their participation in it—runs through otherwise very disparate works, most notably François-Gérard Jollain’s promotional or “bullish” Commerce between the Indians of Mexico and the French at the Port of Mississippi (ca. 1719) and Bernard Picart’s “bearish” Monument Dedicated to Posterity in Commemoration of the Incredible Folly Transacted in the Year 1720. This comparative approach invites the reader to look at familiar prints in new ways, as in the case of Dubin’s thought-provoking inclusion and recontextualization of three versions of Picart’s Monument (figs. 13, 19, and 23), the work that has been reproduced, translated, and commented upon more frequently than any other bubble print.

Bernard Picart, Monument Dedicated to Posterity in Commemoration of the Incredible Folly Transacted in the Year 1720, Muller 18, from Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid, Amsterdam, 1720, etching and engraving. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT (photograph provided by Yale University Library)

“Cast of Characters,” written primarily by Martin (with contributions by Dubin and Viljoen), draws on the theatrical dimensions of the Tafereel and consists of twelve vignettes that spotlight historically and iconographically representative figures, a literary device that allows the authors of Meltdown! to use a variety of rhetorical styles and weave numerous threads and secondary sources together succinctly and efficiently.

Martin sets the stage skillfully with her sketches of the three main characters: “John Law, or, The Gambler,” “Madame Law, or, Madame Compagnie,” and “The Banknote.” In the first vignette she observes that the formal portrait of Law as controller general that is often found at the beginning of the Tafereel is not just an exercise in self-promotion. It accords Law’s System the gravitas of a religious framework, a parallel easily (and often) missed, in spite of the presence of the Eucharistic symbols identified by Dubin in the first chapter. Martin also relies artfully on little-known examples of medals and tobacco boxes that reference Law’s portrait to reveal what prints often hide, most notably the human costs of the exploitation of the New World. Such objects, she rightly notes, also bring to light “how truly far the bubbles spread as a multimedia event” (53).

In the second vignette Martin analyzes two almost identical 1720 engravings by Claude Duflos: Winter, after Rosalba Carriera, and Madame Law. She pays close attention to the iconography of the prints, shown side by side, and invites the reader to linger on the two images. She then places the prints in the larger context of the participation of women in the bubble economy.

“The Banknote” is a first-person narrative told from the point of view of a banknote. Inspired by eighteenth-century it-narratives, this third vignette highlights the close ties between literary and visual representations of the bubbles of 1720. It also accentuates the fictional nature of the new economy and the sense of wonder, magic, joy, and possibilities the bubbles generated. Additionally, it introduces an important and enjoyable counterpoint to the gloom cast by many Tafereel prints.

Taken as a whole, “Cast of Characters” underscores the many complexities involved in interpreting bubble prints and the value inherent in studying the Tafereel from the perspective of art history. Dubin’s multilayered contextualization of “Fortuna,” a central icon of the Tafereel, is a case in point. Her ancient association “with the waxing and waning of the sea” points to the importance of global trade (90). Her sensuous appearance explains why the credit on which global trade depends came to be gendered as female. In addition, Fortuna’s association with the ancient and modern tropes of female seduction and betrayal allowed Picart to signal almost casually in the Monument that there is a relatively simple explanation for the otherwise unaccountable folly of 1720: the fickle—that is, “female”—nature of economic and artistic signs.

In the last chapter, “Collecting in Vain: Fools, Cons, Devils, and Dupes in ‘The Great Mirror of Folly,’” Viljoen contends that the print section of the Tafereel does not consist, as is frequently assumed, of disparate images that happen to be tied thematically to the events of 1720. Instead, she argues, one should think of the Tafereel as a curated collection, or recueil. Specifically, she demonstrates that the Tafereel evinces a clear “partiality for compositions that evoke [Hieronymus] Bosch, [Pieter] Bruegel, and [Jacques] Callot” (115), who, more than other earlier artists, would have been associated by eighteenth-century connoisseurs with the kind of carnivalesque, scatological, and detail-filled scenes showcased throughout the Tafereel. The latter include many representations of worthless shares floating in the wind, which echo the frequent depictions of throngs of visually undifferentiated investors. In addition, given the extent to which Bosch, Bruegel, and Callot were known to have participated in an economy of piracy and counterfeiting, the pervasive borrowings from this trio of artists found throughout the Tafereel reenact the many kinds of frauds investors engaged in and fell victim to.

Meltdown! Picturing the World’s First Bubble Economy succeeds brilliantly in introducing the bubbles of 1720 and their iconography to readers who may not be familiar with them while also offering interpretations that enrich specialists’ understanding of the contributions made by visual and material culture to our knowledge of a pivotal moment in economic and world history. The Tafereel was ostensibly conceived as a “warning to posterity.” By contrast, Meltdown! invites readers of this captivating volume and, hopefully, future visitors to the companion exhibition (titled Fortune and Folly in 1720 and, as of this writing, slated to be on view in fall 2022) to celebrate the rich visual culture of the first bubble economy and its ongoing relevance.

Catherine Labio

Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Colorado Boulder