- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The year 2018 marked the three-hundredth birthday of London cabinetmaker Thomas Chippendale (1718–1779), whose legacy embodies an international style as much as actual designs and examples of furniture. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent exhibition celebrated the master while also reflecting on the cultural relevance of antique furniture today. Tucked into the American Wing’s Virginia and Leonard Marx Gallery, the two-room exhibition offered a brief examination of Chippendale’s original pattern books along with an assortment of furniture created in the cabinetmaker’s style. Why should an American museum pay homage to an eighteenth-century British cabinetmaker? What did visitors, including those uninitiated in the study or connoisseurship of decorative arts, learn from this exhibition?

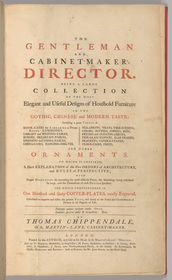

The exhibition began by summarizing Chippendale’s curriculum vitae. The Yorkshire-born cabinetmaker migrated to London around 1748, a period of wide commercial expansion in the city and throughout the British Empire. Faced by increasing competition within London’s growing luxury furniture trade, Chippendale rose to prominence after publishing his first pattern book, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, in 1754. Featuring 160 drawings of furniture and architectural elements, the book sold by subscription to England’s aristocracy and wealthy mercantile elite and illustrated Chippendale’s keen awareness of his clients’ lifestyles and aesthetic aspirations. As the curators, Femke Speelberg, associate curator of drawings and prints, and Alyce Perry Englund, associate curator of the American Wing, explained on the introductory panel: “Chippendale’s designs . . . spread through the British Empire, following the routes of the nation’s expanding maritime trade and colonization of North America and the Caribbean.” British and American cabinetmakers quickly interpreted the designs in both sophisticated and provincial ways. Chippendale’s name soon “came to refer not just to a prominent London cabinetmaker, but also an enduring style, one that played a central role in British and American furniture design for more than 250 years.” The curators concluded the introduction by emphasizing that the exhibition “explores how he came to create the Director during his early years in London and how the book’s widespread influence afforded the iconic status he enjoys to the present day.”

Chippendale’s iconic status must be viewed through the time and place from which he emerged. Chief among the reverberations felt in London during the 1740s and 1750s was the increasing use of printed trade cards, broadsides, advertisements, and designs as commercial vehicles. Following passage of the 1735 Engravers Copyright Act, which protected original works from unauthorized publication, came a steady stream of printed designs. The exhibition’s first gallery, cleverly located in an American Wing period room permanently decorated with eighteenth-century wallpaper, set the stage with a vivid example of the influence that published prints swiftly exerted around the world. The dazzling English wallpaper embellished with bold grisaille scenes drawn from eighteenth-century French and Italian prints, immediately underscored the commercial impact of prints on European and American interiors. Made between 1765 and 1769, the yellow and blue wallpaper originally adorned the entry hall of an elite colonial home, the Van Rensselaer Manor House in Albany, New York. The papered walls surrounded five cases, four of which were dispersed in the gallery’s corners and a fifth positioned in the room’s center with a cluster of furniture. Each outer case held key design predecessors to Chippendale’s eponymous book. The parade of canonic seventeenth- and eighteenth-century architecture and design treatises included continental table designs and ornamental patterns by French engravers Daniel Marot and Jean Berain and British works such as Colin Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus (1715), John Vardy’s Some Designs of Mr. Inigo Jones and Mr. Wm. Kent (1727), Matthias Lock’s Six Sconces, and Matthew Darly’s A New Book of Chinese Designs (1744). These historical works were arrayed around the core assemblage: a 1754 edition of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director placed in front of tiered platforms displaying three period side chairs. Although the celebrant’s book was overshadowed by the elevated chairs, it was set amid prime examples of Chippendale’s impact on British and colonial furniture. Visitors stood face-to-face with a carved Neoclassical chair with a fan-shaped backsplat attributed to the master’s own workshop from about 1772. Inspired by the cabinetmaker’s designs for “Ribband back chairs” was an elaborate colonial side chair made in Philadelphia and attributed to the prominent cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph. Leaping ahead two centuries, Chippendale’s influence on twentieth-century American design was represented by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s laminated wood “Chippendale” chair from 1984.

Distinct examples of the pattern book’s immediate influence populated the second gallery, which also featured an impressive assemblage of eighteen preparatory drawings. Along the walls that surrounded the sketches were eighteenth-century American and British chairs, tables, mirrors, and shelves inspired by the Director and period portraits of wealthy Americans sitting on or standing in front of elegant, Chippendale-style furniture. As announced in the 1754 pattern book’s subtitle, Chippendale offered “Gothic” designs that incorporated patterns of trellises, elongated spires, and pointed pendants and arches; “Chinese” furniture and ornament with pagodas, bamboo lattice and fretwork patterns, and Chinese-attired figures; and “Modern” interpretations of curvilinear floral and foliate designs that comfortably fit within English expressions of the French Rococo. The furniture displayed echoed the exhibited drawings and styles Chippendale promoted. A carved chest-on-chest by Philadelphia cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck (who emigrated from Scotland in 1763) stood perpendicular to Chippendale’s preliminary drawings of chests and commodes. A drawing of a tiered china case hung directly across from an airy Chinese-style standing shelf made by the preeminent London cabinetmaking firm of William and John Linnell. Even more arresting, a drawing of pier glass frames reflected, literally and figuratively, a boldly carved, framed pier glass mounted on the opposite wall. The gallery concluded with two important codas to the eighteenth-century works: a genteel Neoclassical revival side chair created between 1902 and 1908 at Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Tiffany Studios (a succeeding icon and branding legacy) provided a brief emphasis of the introduction’s premise and twentieth-century books that testified to Chippendale’s lasting presence, including Hugh Troy’s 1941 satirical tale, The Chippendale Dam.

The broad significance of Chippendale’s designs is underscored in the exhibition’s accompanying catalogue. “Chippendale’s Director: A Manifesto of Furniture Design,” an issue of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin by Morrison H. Heckscher, curator emeritus of the American Wing, presents the captivating history of the publication. As Heckscher explains, the Director was issued as sets of drawings in two volumes in 1754. The pattern book was later reprinted in 1755. Chippendale revised and created new designs between 1759 and 1762, when the third, larger compendium was published. Heckscher also recounts how the volumes and preparatory drawings were acquired for the Metropolitan Museum’s young prints and drawings collection in 1920 by its visionary curator William M. Ivins Jr., who developed the holdings into an acclaimed repository of works on paper.

Chippendale’s tercentennial afforded British and American museums with opportunities to display furniture made or inspired by the master. Although engaging and attractive, the exhibition’s limited size and scope, and somewhat hidden location, reinforced a conventional view of antique furniture and minimized the endurance of Chippendale’s groundbreaking publications. As a result, the tribute sidestepped meatier historical comparisons that could have driven home the very wide reach Chippendale’s work has exerted across centuries and continents. Chippendale-style furniture, especially interpretations of his “Ribband back” chairs, is regularly sold by online retailers such as 1stdibs or Joss & Main, or at national furniture chains like Raymour & Flanigan. While the exhibition helped to reverse the belief that eighteenth-century side chairs, high chests, and tea tables are more than collections of “old, brown stuff,” the somewhat predictable display of mostly period furniture did only limited justice to the true impact and diffusion of Chippendale’s designs. I wondered, for example, if the captivating preparatory drawings displayed in the second gallery would have lost their aesthetic power if they had been interspersed among the furnishings rather than grouped and exhibited opposite them? Taking a lesson from the museum’s Heavenly Bodies costume exhibition, open during the first half of this exhibition’s run, Chippendale’s “Director”: The Designs and Legacy of a Furniture Maker could have illustrated the pattern book’s true relevance by extending its displays into other parts of the American Wing. A walk through the wing’s period rooms and Luce Center immediately illustrates the impact Chippendale’s designs exerted on American decorative arts. Case after case of carved mahogany chairs made during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries sport Chippendale-type ribband backsplats and anamorphic horse legs, while numerous tea tables and high chests possess pagoda-topped serpentine stretchers and curled ogee-bracket pediments similar to those designed by Chippendale.

The exhibition also quietly underscored Americans’ long fascination with international, celebrity designers, a point not addressed by the displays or in the explanatory text. Long before Phillipe Starck’s ghost chair, Prada’s nylon bags, or even Tiffany Studios’ leaded glass lamps became iconic, eighteenth-century design innovators such as Josiah Wedgwood and Matthew Boulton, like Thomas Chippendale, captured European and American audiences with their ceramics, metalware, and furniture. Few people may be aware of the histories of these firms today, but many consumers readily recognize their names.

Despite only a few examples of twentieth-century prints or furniture exhibited in the galleries, Chippendale’s reach extended far beyond Rococo and Neoclassical revivals. With the exception of Venturi and Scott Brown’s “Chippendale” chair, newer examples of his influence barely made an appearance. Where was a photograph of Philip Johnson’s bracket-topped AT&T building, built on Madison Avenue also in 1984? A display of additional contemporary iterations of Chippendale’s designs would have firmly secured his status as one of the modern world’s earliest international designers and an important precursor to today’s design celebrities and global brand names.

Debra Schmidt Bach

Curator of Decorative Arts, New-York Historical Society