- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Before viewing any of the artworks in the exhibition, visitors to Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots at the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) encounter a wall-sized, vertically oriented black-and-white photograph of a denim-clad Jackson Pollock, hammer in his back pocket, leaning closely to inspect the surface of one of his black enamel paintings. The painting he scrutinizes, Number 22, 1951, hangs in bright sunlight on the exterior wall of a wood-shingled barn. His forehead seems almost to touch the canvas as his body casts a gray shadow over the majority of its surface. A reproduction of this previously unpublished photograph, a gelatin silver print made by Hans Namuth in 1951, likewise provides a visual initiation to the exhibition catalogue.

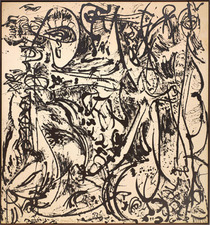

Namuth’s photograph functions as a thesis statement for Blind Spots, an exhibition with two primary objectives: to prioritize a period in the artist’s career that has been overlooked in the history of other Pollock retrospectives, and to allow for the public’s careful study of these works in the flesh, unglazed and numerous. Most of the thirty-two “black paintings” or “black pourings” exhibited at the DMA are from 1951, immediately following the period of 1947 to 1950 in which Pollock secured his place in the public imagination as the radical innovator of gestural, abstract, allover compositions in poured and splattered “skeins” of oil and enamel paint.

The existing critical record suggests ready interpretations for Pollock’s black-painting period, which extended from 1951 to 1953, and Gavin Delahunty, the DMA’s Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art, has had to contend with these repeatedly in public statements and interviews since the exhibition first debuted at Tate Liverpool last summer. In one such interpretation, the works are a conscious “reduction” of artistic means on Pollock’s part—a restriction of his color palette to include only black, and a simplification of his surface structure to consist of just two layers: the enamel figure and the canvas ground. This theory might be attractive to Pollock’s black-painting apologists, because it positions him at the forefront of coming trends in self-consciously reductive art. Though hints of such an interpretation do appear at rare moments in the catalogue, such as when Delahunty suggests a comparison to Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings of the mid-1950s, overall the exhibition does not suggest a narrative of so-called artistic reduction in Pollock’s later works.

In a statement that predates any of the works on display, Clement Greenberg judged that despite the artist’s use of brightly colored paint, “Pollock remain[ed] essentially a draftsman in black and white who must as a rule rely on these colors to maintain the consistency and power of surface of his pictures” (Clement Greenberg, “Review of Exhibitions of Jean Dubuffet and Jackson Pollock,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O-Brian, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, 124). In other words, for Greenberg, Pollock’s pre-drip painting was “essentially” drawing in black and white. His description is reductive, though the paintings it refers to are not.

Blind Spots, spread in more or less chronological order over nine partitioned rooms of the DMA’s Chilton Galleries, contextualizes the monochromes by displaying them among a few of Pollock’s earlier paintings and experimental ink drawings. The exhibition begins with pieces that predate Pollock’s black works, including six “drip” paintings, the majority of which come from the years 1949 to 1950, with the exception of Cathedral (1947) from the DMA’s permanent collection. None of these are as large as Pollock’s best-known drip paintings of 1950 (e.g., Lavender Mist: Number 1, 1950 and Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950), and unlike those mural-esque works, most assume a vertical orientation. Importantly, each contains dripped networks of black enamel in addition to their respective non-black hues. Any gradation that occurs between colors and values in these paintings happens either optically—in the viewer’s eye, though not on the canvas itself—or by the chance mixing of multiple, overlapping strands of wet-on-wet paint. This is true of the works that take a more varied palette (e.g., Number 34, 1949; 1949), as well as those that tend toward a grayscale scheme of blacks, grays, silvers, whites, and off-whites (e.g., Cathedral and Number 2, 1950; 1950). One gets the sense from these works that Pollock’s move to black was not a significant turn away from a sophisticated engagement with the color-specific problems of traditional painting. The differing color schemes contribute to the legibility of each artwork’s individuality (i.e., it is easy to remember that Number 3, 1949: Tiger (1949) is the one with orange and black drips), but color also has the potential to distract from differences among their compositions and marks.

Compare Greenberg’s statement above to artist Lee Krasner’s description of the black enamel paintings at an exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery: “The 1951 show seemed like monumental drawing, or maybe painting with the immediacy of drawing—some new category” (B. H. Friedman, “An Interview with Lee Krasner Pollock,” in Jackson Pollock: Interviews, Articles, and Reviews, ed. Pepe Karmel, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1999, 36). Though she relates Pollock’s painting method to drawing, as Greenberg did before, Krasner’s description is generative rather than reductive. Describing Pollock’s new method of using an enamel-loaded turkey baster to drop and drag his marks, she said, “His control was amazing. Using a stick was difficult enough, but the basting syringe was like a great fountain pen. With it he had to control the flow of ink as well as his gesture” (Friedman, 38).

Pollock’s drawing practice plays a large part in the DMA’s contextualization of the black enamel paintings. A double room in the exhibition is devoted to the artist’s ink drawings on paper. As the wall text explains, sculptor Tony Smith gave Pollock a large stack of Japanese mulberry paper as a gift at the beginning of 1951, and Pollock’s free experimentation with this particularly absorbent surface likely inspired his earliest engagement with unprimed canvas later that year.

Viewers at the DMA encounter these ink drawings after already visiting three rooms of black enamel paintings. The visual comparison between the two bodies of work is made in reverse chronological order, so as to avoid arguing too insistently for the possibility of a cause-and-effect relationship between them. Rather, each group may be experienced on its own material terms.

As ink rests both on and in the fibers of the mulberry paper, so too do the strokes of Pollock’s black enamel “fountain pen” penetrate the fabric of the unprimed canvas to produce a matte, dyed look. The dark liquid paint, combining with the beige of the raw cotton cloth, produces a subtle spectrum of dark gray-browns. In moments where the artist’s gesture slows down, idles, or makes multiple passes, the enamel accumulates on the surface to produce shiny areas. With the sensitive control of his stylus, and the variety of his marks, Pollock took advantage of the properties inherent to his fluid, synthetic medium to discover unexpected depth in the literal surface of the unprimed canvas.

Such material effects constitute the characteristic graphic and painterly qualities of the black paintings of 1951. The exhibition’s first examples of this description hang among paintings on primed canvas from the previous year. Where Pollock’s enamel meets the non-porous surface of the earlier primed canvases, it tends to produce an effect that is truly black and white, a simpler two-layered construction of black figure on white ground. Having been “primed” by such comparisons in the earlier galleries, the viewer reaches the sixth room of the exhibition, where all seven large black paintings employ unprimed canvas. Pollock appears here, not as an imposer of chromatic reduction, but as a conscious, well-practiced manipulator of sensuous materials.

Another major interpretative assumption that Blind Spots must contend with is that Pollock’s black paintings signaled a radical reintroduction of figuration to his personal oeuvre and to an art world dominated by abstraction. The exhibition addresses Pollock’s supposed turn to figuration by arguing instead for the pervasiveness of the figure throughout Pollock’s career. Presumably it is to this end that the first gallery shows two figurative ink drawings from the early 1940s—one on paper and the other using a collotype print as its substrate, the photograph itself a double portrait. Another ink drawing on paper from 1947 is displayed among the first black paintings in the exhibition. Its date and its particular forms (e.g., a vague arm shape, areas of relatively dense scribbles that become masses, heavier and lighter repetitive marks that take on a particular personality or character) attest to Pollock’s developing tendency toward black-and-white quasi-figuration at the same time that he began making allover drip paintings. Here as elsewhere, Blind Spots allows cross-medium study to challenge a strict narrative of stylistic periodization.

The earliest work in the exhibition is a three-dimensional stone sculpture that Pollock made as a teenager. The small, ovoid carving takes the form of a human head on its side. Though it is the first piece in the exhibition chronologically, it too appears among the black paintings of the early 1950s. Its strong figuration spreads to the surrounding canvases to suggest possible figures emerging in black enamel. The four other sculptures in the exhibition, made in 1949 and 1956, seem to perform a similar role, presaging or echoing the forms that take shape in the paintings.

Importantly, Pollock saw his engagement with recognizable imagery in the black paintings as a passive, psychophysical response to circumstances arising within the canvas and in the moment of painting. “I’m very representational some of the time,” he said, “and a little all of the time. But when you’re painting out of your unconscious, figures are bound to emerge” (20). His statement recalls Freudian and Jungian psychoanalytic exercises in free association, where the patient responds to verbal stimulus with enough immediacy to remain passive to the situation, producing a word (the verbal equivalent of figuration) that originates in the subconscious. Neither Pollock nor the patient begins the exercise with a preconceived image, yet the conditions imposed by the exercise itself make the emergence of images likely. Pollock did not make preliminary sketches for his paintings because he wanted to approach them as directly as he approached drawing, where figuration and abstraction coexisted for him. Looking at the black paintings in Blind Spots, one gets the sense that Pollock did not feel a strong binary distinction between drawing and painting, nor between abstraction and figuration.

The final works of the exhibition are those Pollock painted after his panned solo show at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951. In 1952, the artist sought new representation with Sidney Janis and began producing paintings where black enamel again appears together with color. Non-figurative drip techniques and oil paint reappear too. Because Blind Spots focuses on the black paintings of 1951 and their negative reception, these final paintings seem to present a collection of conciliatory gestures extended by Pollock to an art establishment who so disapproved of his reductive figuration.

Jeannie McKetta

PhD candidate, Department of Art and Art History, University of Texas at Austin