- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

A survey of thirty years’ work by one of New Zealand’s most prolific photographers required agonies of curatorial selection. Fiona Pardington and curator Aaron Lister collaborated for over two years, choosing works not only from institutional and private collections but also from boxes unearthed from under beds. Inevitably, curation becomes an exercise in synecdoche; each selection is a tip-of-the-iceberg gesture standing in for some facet of an extensive oeuvre. The combination of abbreviation and juxtaposition can be dizzying. It also has the intended effect of shifting the focus from the works to the artist, thereby revealing the persistent preoccupations with mortality and memory that bind together Pardington’s diverse practice. Photography, death, and remembrance, as Roland Barthes pointed out in Camera Lucida (trans. Richard Howard, New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), have a mysterious tripartite relationship that Pardington has consistently explored.

Pardington’s projects resist tidy chronology, which, in any case, she rejects as “dreadfully dreary” (Pardington quoted in Kate Brettkelly-Chalmers, “A Conversation with Fiona Pardington,” Ocula [September 2, 2015]: https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/fiona-pardington/). History, nevertheless, makes its presence felt. For instance, a surprisingly generous allocation of space is dedicated to problematics of the “gaze.” This feminist preoccupation seems passé nowadays, but in the 1980s, when other New Zealand photographers were on the streets shooting social documentary, it signaled an intellectual engagement with what photography was rather than what it recorded. The works here include simplistic sex-object gender reversals from the 1980s, such as Prize of Lilies (1986); more disturbing interrogations of violence and complicity, such as Choker (1994); and a selection of 1950s soft-porn repurposed for the series One Night of Love (2001). In this series, rephotographed photographs come with the scars of their former physical existence: a scratched-off blob on Fifi’s soft-porn nether regions hints at alternative uses for her two-dimensional charms; the rejected contact prints of Renee, Layla et al., defaced with editorial cross-outs, eloquently express the disposability inherent to commodification. Pardington says that she invented names and backstories for these working women, thus reaching beyond the simulacra to the person who once breathed on the other side of the camera lens. But by providing her unknown models with stage names suggestive of the Playboy sensibility of the period, she also seems to be uncritically reproducing the myth.

In other parts of the exhibition, Pardington explores her reconnection to her Māori heritage; she is of Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Kahungunu descent. The so-called archival turn of the 2000s had other New Zealand photographers—Mark Adams and Fiona’s brother Neil, for instance—rummaging through the storerooms of museums, literally bringing to light the detritus of imperial and colonial collecting mania. These photographers take deadpan images of museum scenes—cupboards of stuffed birds; the labeled backs of carvings; towers of storage drawers—and present them in a flatly lit, deliberately non-aestheticized manner.

Pardington also ventured into museum archives, but her engagement with their contents is steeped in a spiritual sensibility. With immense technical skill, she coaxes magnificent enlarged images from Māori taonga (cultural treasures) found in museums. Ake Ake Huia (2004), for instance, shows the white-tipped black tail feathers of the now-extinct huia bird. The feathers were reserved for high-ranking Māori; special containers—waka huia—were carved to house them. They were also significant in mourning ceremonies, adorning the sacred head of the deceased. That the huia became extinct in the early twentieth century was not due to these indigenous ceremonial uses, however, but rather to the depredations of European collectors and colonial habitat destruction. So the mourning role of huia feathers is here poignantly doubled back on itself. It might have been helpful if the wall label had provided some, or indeed any, of this information, but there seems to have been a tactical decision not to overburden the images with text. Many gallery visitors may already be familiar with this more substantial description, but surely not all; tourists must be bemused.

Nearby is a series of seven photographs of orphaned heitiki (greenstone carvings) recovered from the storerooms of the Auckland Museum. They seem to swim blurrily upwards toward the light from the depths of forgetting, as if Pardington’s camera has called them back into the living world from the limbo of archival drawers and boxes. Again, the viewer is expected to already know the actual dimensions, material, and significance of these very personal adornments for Māori, and hence to understand the poignancy of their museological anonymity.

Pardington’s practice, in short, is poetic and allusive rather than documentary. Hand-developed, the photographs of this period bear the marks of their making. The artist deliberately left the edges of the negative visible, thus making it clear that this is art, not ethnography. The massive enlargement and luscious printing also endow these objects with the gravitas of holy relics.

These latter characteristics are also evident in three digital images—front, back, and profile views—of Matoua Tawai’s plaster-cast tattooed head. The photographs were part of a substantial series of enlarged prints of Pierre Marie Dumoutier’s phrenological life casts of Māori and Pacific people created on Jules Dumont D’Urville’s South Seas voyage of 1837 to 1840. The reduction here to just one individual and three photographs narrows the focus. Art historian Roger Blackley has written of the “moody neo-classicism” invoked by enlarging these heads and draining their color (“Metamorphosis,” Landfall Review Online [September 1, 2011]: http://www.landfallreview.com/metamorphosis/). In the case of Matoua Tawai, this near-monochrome treatment is intensified by the unusually pale buff color of the original cast, which Pardington further bleached and set against a velvety black background. When she took the photograph, Pardington believed this man to be a chief, as were the other subjects of the Māori life casts she photographed in the collection of the Musée de l’Homme. But Dumoutier cast the face of this particular man in the Bay of Islands in 1840 where, as Blackley points out, trade in moko mokai—preserved tattooed heads sought after by European collectors—had been roaring. Blackley suggests that Moutou Tawai may have been a captive slave of the Ngāpuhi tribe, coerced into receiving the moko by the tribesmen who had the enterprising intention of subsequently relieving him of his head and selling it. While the revised story makes no difference to the dignity of the man displayed, it does hint at layers of entrepreneurial chutzpah otherwise absent from the superficial tale of indigenous submission to European scientific acquisitiveness. Oddly, the wall label both acknowledges and obfuscates this alternative history, acknowledging merely that Moutou Tawai may have been posing as a chief, as if he, a captive, had any say in the matter.

If the image of Moutou Tawai is pale and interesting, the photographs in the adjoining space explode with experiments in florid color, featuring lurid museum curios spilling out from black backgrounds; orange toadstools; a plaster-cast head floodlit with indigo; and sickly green, deformed animal fetuses. But the impulse to aestheticize and poeticize rather than document or explain is still present: enlargement, lush lighting, black backgrounds, an aura of elegy—all boxes ticked.

A pair of images in this section marks Pardington’s most recent forays into the archive. Excerpted from the series Childish Things (2015), these are much-enlarged segments from a young boy’s letters to his uncle in the 1860s, which were found among the papers of his father, the physician and photographer Alfred Charles Barker of Canterbury, New Zealand. The letters are written on lined schoolroom paper with a quill pen, but Pardington cropped and magnified the child’s misspelled writing such that only a word or phrase confronts the viewer. One of these words is “photography”—a technical term coined only twenty-odd years earlier, and tricky for a child to spell. Indeed, the lad made a hash of it, but he laboriously and neatly corrected his errors. In a nod to Colin McCahon (another New Zealand artist fascinated by the expressiveness of handwriting and its relationship to the self), the other photographed and enlarged phrase is “I am.” It too, tellingly, contains a crossed-out, corrected stumble. Pardington has captured how handwriting and photographic portraits share that poignant Barthesian “this-has-been” quality. Young Arthur Llewellyn Barker, with his inky fingers and tongue stuck out in concentration, was really once present and is now dead.

Gaudiness is (mostly) reined back in the latest, largest, and most elaborate of the still lifes: the jewel-like series that hangs in the centerpiece of the gallery against rich blue walls decorated with the romantic font used for the show’s title. These complex assemblages are homages to the Dutch sixteenth- and seventeenth-century vanitas tradition. They share a piling up of detail on detail and trompe l’oeil qualities. Yet in Pardington’s case, the hyperrealism of Willem Claeszoon Heda or Jan Vermeulen is mischievously turned back on itself; this luscious photographic verisimilitude is indeed a photograph. Pardington has also experimented with printing onto a gesso ground that gives a hard matte finish, which only increases the painterly look—one almost peers closer to try to see nonexistent brushstrokes.

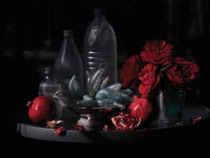

Here the artist has emerged from museum storerooms and stepped onto the windswept coast of Northland. Instead of huia feathers, plaster-cast heads, specimen jars, and dusty mushrooms, she plucks detritus and dead birds from the sand and arranges them with exquisite care alongside treasures from her life: a pounamu pendant, a note in her mother’s handwriting, coral from the Cook Islands, her grandmother’s crystal bowl, her mother’s roses. Colors glow in morning sunlight. Plastic bottles washed up on Ripiro Beach are somehow rendered as glisteningly beautiful as pomegranates. Equal weight is given to all elements; no value judgements are made between a family heirloom and a dead albatross’s tail feathers. Yet there is an implicit environmental comment in gathering garbage washed ashore from all over the globe. The intensely personal nature of these tabletop topographies is not immediately evident, but every component has talismanic significance. Even the water in the vessels has a named source and was carefully transported from elsewhere.

Pardington’s unashamed, lyrical romanticism stands out in a contemporary art world wary of beauty and inclined to treat it with irony or as kitsch. But Pardington’s work is neither ironic nor kitsch. The title of the show—A Beautiful Hesitation—is Pardington’s own description of photography, reflecting not only the temporal stutter of the shutter but also the loveliness that she finds in that “capacious medium” (Pardington quoted in Brettkelly-Chalmers). Yet the urge to aestheticize invites unease. Glamour has an etymology rooted in enchantment and disguise. Some frown when historical objects are decontextualized as art. Brian Brake, for instance, has been criticized for romanticizing Māori taonga using similar techniques to Pardington. (Damien Skinner provides a nuanced, historicized view of Brake’s approach in “Object Photography,” in Brian Brake: Lens on the World, Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2010, 283.) Does a surfeit of beauty tell lies or reveal new truths?

Stella Ramage

Research Assistant, Art History Program, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand