- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

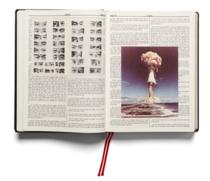

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s Holy Bible takes the form of a King James facsimile, complete with tissuey paper and gilt edges. Opening the book reveals photographs printed as if pasted over the text, with evocative scriptural phrases underlined in red. A crimson pamphlet in the back bears the essay “Divine Violence” by philosopher Adi Ophir, which argues that the biblical God regulated humanity through catastrophic violence, and that with the rise of law and the nation state, this power shifted to the human realm. This very human condition is manifested in the compelling documentary photographs, chosen by the artists from a collection named the Archive of Modern Conflict (AMC).

Broomberg and Chanarin were inspired to do the project while researching War Primer 2, an altered version of a photobook by Bertolt Brecht. First published in the German Democratic Republic in 1955 as Kriegsfibel, Brecht selected, arranged, and obliquely annotated a series of war photographs clipped from diverse newspapers and magazines, often including fragments of the ambient captions. The result is an understated yet scathing critique of ostensibly “straight” documentary photography. Broomberg and Chanarin revised the work for a post-9/11 world by purchasing one hundred copies of an English-language edition and then painstakingly overlaying and overprinting the pages with photojournalistic images related to the so-called war on terror.

In the process, the artists came across a Bible that Brecht had repurposed into one of many notebooks, evinced by pasted-in press images and handwritten notes. Thus Holy Bible complements War Primer 2 as a powerful homage to Brecht’s prescient suspicion of photographic truth. It is also a work fully in line with Broomberg and Chanarin’s practice, which critically engages with the social economy of images.

The reader first encounters conflict just by picking up the book, expecting a Bible and opening it to find a turf war between contemporary, contingent photographs and ancient, ostensibly immutable scripture. In many of the images, catastrophe is self-evident. We see corpses and blood, war and its aftermath. Yet the most intriguing images are those in which the notion of conflict is latent. A couple kisses. A boy holds balloons. Tiny creatures swim in a microscopic landscape. Where is the conflict? Potentially everywhere, they seem to say. It all depends on who is shooting (images, guns) and who is publishing, reading, and ultimately archiving. We realize that in biblical terms the world’s first conflict concerned a tree of knowledge.

Self-references to media amplify the theme. One image shows a man piggybacking on another to point a film camera in a bus window. In another instance, a spread shows a photo of what looks like a corpse on the left page, with a photo of the setup of that photo on the right. Most powerfully, we see only the back of one particular image, bearing inscriptions, stamps, and finger prints. The markings reveal that we are “looking” at a photo of corpses at Buchenwald. The underlining of text, which evokes both the medieval rubric and Bible study sessions, serves as an ironic, appropriated take on conventional image captioning. Artifactual red crop marks on some of the photos echo this while simultaneously resembling bloody slashing, as when a head is separated from its body by a grease-pencil guillotine. We become mindful of photographic terms connoting violence (shoot, capture, blow-up, crop, bleed, and, most recently, photobomb).

Holy Bible, like its namesake, culminates in Revelations. This last book of the New Testament is a story of vision, specifically a vision of the apocalypse in which powerful beasts demand worship but are ultimately defeated as false prophets. The section opens with an artful studio photograph of an egg swaddled in transparent film and is paired, appropriately enough, with the underlined phrases “the beginning” and “Write the things which thou hast seen, and things which are, and the things which shall be hereafter” (713). Successive images include what looks like a bomb-sniffing robot (“beasts full of eyes,” 714), a spy plane and its cameras (“the image of the beast,” 717), and the obligatory World Trade Center shot (“worship the beast and his image,” 718). In a final, intriguing image, the ostensible clarity of photojournalism gives way to overt illegibility. We could be looking at the visual trace of a fluttering bird, smoke, votives, windows lit from within, or something else entirely. Paired with the phrase “bottomless pit” (720), the choice of abstraction appears to reiterate the idea that photography is the false prophet, ultimately an illusion of human perception.

The book, like the Archive of Modern Conflict and fellow travelers through what can be called the archival turn, is concerned with interrogating photography as an institution. In terms of artists’ books in this mode, Broomberg and Chanarin join an emerging canon. Beginning with works such as Andy Warhol’s Raid the Icebox (Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, 1969) and Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (New York: Norton, 1994), the theme flourishes today with Walid Raad and the Arab Image Foundation, Georges Didi-Huberman’s Atlas: How to Carry the World on One’s Back? (Madrid: Museo Reina Sofía, 2010) (click here for review), Andrew Beccone’s Reanimation Library, and the delightful journal Useful Photography, among other efforts. In the digital realm the field is now wide open for artist-publishers, as seen in the work of Wikipedians in residence and the Office of Creative Research.

In this way Holy Bible is especially well complemented by Buzz Spector’s Details: Closed to Open (Swarthmore: Swarthmore College, 2001), a modest book in which the artist embedded with an AMC counterpart, the Swarthmore College Peace Archive. Using details of collection images, Spector created a purely visual sequence of closed fists slowly opening. One might also consider for comparison Klaus Staeck’s Pornografie (Steinbach/Giessen: Anabas-Verlag, 1971), an object lesson in the uncomfortable role of photography in the military-industrial complex. For biblical riffs, look first to David Hammons’s assisted readymade Holy Bible: The Old Testament (London: Hand/Eye, 2002), an ecclesiastical rebinding of the Marcel Duchamp catalogue raisonné.

Repositories such as the Archive of Modern Conflict are crucial to projects like these (note to fellow information stewards: be welcoming). Founded and funded by David Thomson of media conglomerate Thomson Reuters, the AMC began as a collection of images documenting the two world wars. Located in London with storage in two other cities, the archive has been curated for over two decades by former art dealer Timothy Prus. In the process it has become more expansive and more idiosyncratic, comprising over four million photographs with sub-themes including personal photo albums of Nazis and the photography of magic tricks (a form of visual conflict, if you think about it). That the archive is both a product and critique of media was presumably not lost on the artists.

Given this critical framework, one should also consider Holy Bible within the institution of art publishing. In particular, the artists served as creative directors and photographers in the early years of Colors magazine, issued since 1991 under the auspices of the clothier Benetton. The publications have in common the aspiration to take on big issues by subverting mainstream media (book, magazine, press photos) in an expressively rigorous way. Unlike Holy Bible, however, Colors was criticized for its provocative use of media imagery—putting an airplane crash on the cover, for example, with gore cropped out. How does this strategy function differently in the two contexts? To what extent should funding model be a factor in the evaluation of artists’ publishing?

All things considered, Holy Bible is a solid choice for artists’ books collections, where it fits into the traditions of altered books, appropriation, typology, photobooks, institutional critique, and broad political commentary. It is an especially good choice for a teaching collection, on the thinking that the Bible and the twenty-four-hour news cycle are familiar forms through which to introduce artists’ books and critical visual analysis.

One can imagine it working particularly well with students of graphic design and photojournalism. At the turn of the last century a newspaperman writing in dialect as a fictional everyman observed that journalism had developed the power to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Broomberg and Chanarin’s Holy Bible has that power as well.

Jennifer Tobias

Reader Services Librarian, Museum of Modern Art, New York